Navigating the Generative AI Education Policy Landscape

Data Science & AI

May, 2023

Author: Wesley J. Wildman is Professor in the School of Theology and in the Faculty of Computing and Data Sciences at Boston University. His primary research and teaching interests are in the ethics of emerging technologies, philosophical ethics, philosophy of religion, the scientific study of religion, computational humanities, and computational social sciences.

Author: Mark Crovella is a Professor and former Chair in the Department of Computer Science at Boston University, where he has been since 1994. His research interests center on improving the understanding, design, and performance of networks and networked computer systems, mainly through the application of data mining, statistics, and performance evaluation.

Like many institutions, universities are struggling to develop coherent policy responses to generative artificial intelligence amid the rapid influx of tools such as ChatGPT. Higher education is not known for its ability to respond nimbly to changes wrought by emerging technologies, but our experience thinking through and forming policy at Boston University — in dialogue not just with administrators and faculty colleagues, but also, crucially, with our students — points toward an opportunity to step back and reassess what our goals are as institutions of higher learning and how we can best achieve them. In this article, we describe the policymaking process at BU and the implications each of us is thinking through as instructors of writing and computer languages, two domains that generative AI is poised to disrupt in major ways.

Generative AI has catalyzed a rare degree of intense discussion about pedagogy and policies.

A recent letter signed by over 27,000 leading academics and tech entrepreneurs calls for a pause on advanced AI development. (It’s important to note that plenty of their colleagues have opted not to sign, or have critiqued the letter). There is indeed reason to worry about both widening economic disruption caused by generative AI and the arrogant or naive belief that the market will self-regulate and nothing too terrible can happen. And while the letter does raise awareness about the dangers of AI, the “pause” the letter calls for is highly unlikely; companies stand to lose too much market share, and countries too much competitive advantage in research and development, to step out of the AI race willingly. Furthermore, it offers little in the form of concrete steps to move responsible AI forward.

It is against this background that universities are struggling to develop coherent, effective policies for the use of generative AI for text, code, 2D and 3D images, virtual reality, sound, music, and video. As institutions, universities tend to be conservative, multilayered and unwieldy, and well-suited to implementing strategic change over the long-term. They are not so good at adapting to rapid technological change. But this area of policy is particularly urgent, because the assessment of learning has critically depended for a long time on humans performing functions that generative AI can now accomplish — sometimes better than humans, sometimes worse, but often plausibly and almost always faster.

In other words, generative AI has catalyzed a rare degree of intense discussion about pedagogy and policies.

Co-Creating Policy with Students at BU

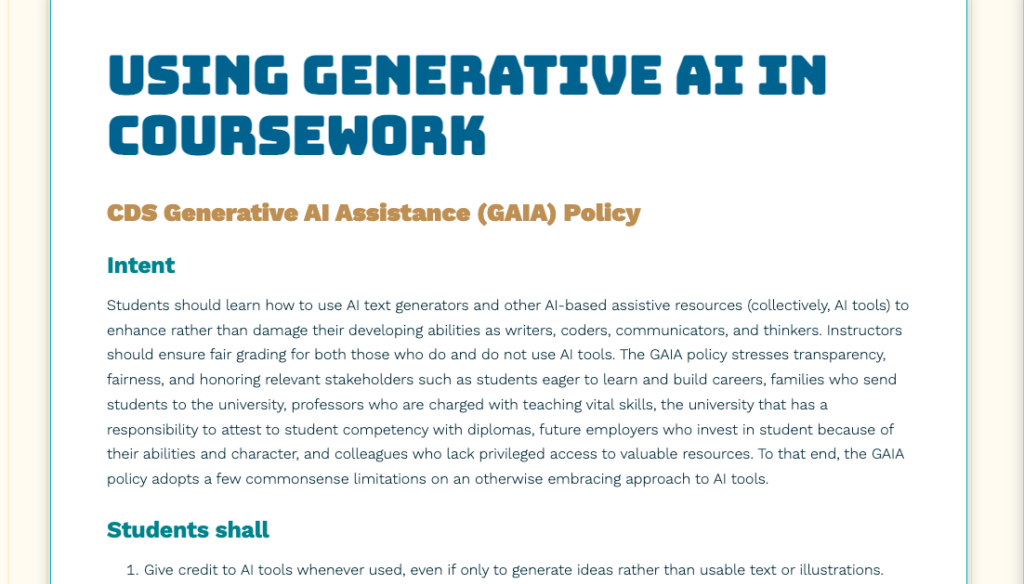

At Boston University, where we teach the ethics of technology, and computer science, respectively, only a few individual university units have had enough time to devise unit-wide policies (most existing policies are for individual classes). Our unit — the Faculty of Computing and Data Sciences (CDS) — started with a student-generated policy from an ethics class (the Generative AI Assistance, or GAIA, policy), which the faculty then adapted and adopted as a unit-wide policy.

The GAIA policy is based on several student concerns, expressed as demands to faculty.

- Don’t pretend generative AI tools don’t exist! (We need to figure them out.)

- Don’t let us damage our skill set! (We need strong skills to succeed in life.)

- Don’t ignore cheating! (We are competing for jobs so fairness matters to us.)

- Don’t be so attached to old ways of teaching! (We can learn to think without heavy reliance on centuries-old pedagogies.)

The GAIA policy also makes demands of students. Students should:

- Give credit and say precisely how they used AI tools.

- Not use AI tools unless explicitly permitted and instructed.

- Use AI detection tools to avoid getting false positive flags.

- Focus on supporting their learning and developing skill set.

Meanwhile, instructors should:

- Understand AI tools.

- Use AI detection tools.

- Ensure fairness in grading.

- Reward both students who don’t use generative AI and those who use it in creative ways.

- Penalize thoughtless or unreflective use of AI tools.

The GAIA policy also explicitly states that we should be ready to update policies in response to new tech developments. For example, AI text detectors that are used to flag instances of possible cheating are already problematic, especially due to false positives, and probably won’t work for much longer.

The GAIA policy is similar to other policies that try to embrace generative AI while emphasizing transparency and fairness. It doesn’t ban generative AI, which runs against the student demand that universities should help students understand how to use such tools wisely. It doesn’t allow unrestricted use of generative AI tools, which runs afoul of the student demand for equal access and fair grading in a competitive job market. It is somewhere in between, which works for now. There are only so many ways of being in between.

The Role of Instructors in the Age of Generative AI

New technologies often create policy vacuums, provoking public interest ethical conundrums — just think of websites for sharing bootlegged music, or self-driving cars. What’s fascinating about the policy vacuum created by generative AI is how mercurial it is. You can throw a policy like GAIA at it and six months later the policy breaks because, say, AI text generation becomes so humanlike that AI text detectors no longer reliably work.

The big breakthrough in AI that led to the current situation was development of the transformer (the “T” in GPT). This approach to deep learning algorithms on neural nets was revolutionary and massively amped up the capabilities of AI text generation. There will be other, similar technological breakthroughs, and it is impossible to predict where they will come from and the effects they will have. Policy targets for generative AI are leaping all over the place like pingpong balls in a room full of mousetraps. Nailing down relevant policy won’t be easy, even for experts.

Educators face the prospect of generative AI short-circuiting the process of learning to think.

New technologies often create policy vacuums, provoking public interest ethical conundrums — just think of websites for sharing bootlegged music, or self-driving cars. What’s fascinating about the policy vacuum created by generative AI is how mercurial it is. You can throw a policy like GAIA at it and six months later the policy breaks because, say, AI text generation becomes so humanlike that AI text detectors no longer reliably work.

The big breakthrough in AI that led to the current situation was development of the transformer (the “T” in GPT). This approach to deep learning algorithms on neural nets was revolutionary and massively amped up the capabilities of AI text generation. There will be other, similar technological breakthroughs, and it is impossible to predict where they will come from and the effects they will have. Policy targets for generative AI are leaping all over the place like pingpong balls in a room full of mousetraps. Nailing down relevant policy won’t be easy, even for experts.

Consider writing. For centuries, we’ve been using writing to help young people learn how to think and to evaluate how well they grasp concepts. Writing is valuable as a pedagogical tool not just because of its outputs (essays), but also because of the processes it requires (articulating one’s ideas, drafting, revising). GPTs allow students to generate the product while bypassing much of the process. Accordingly, instructors need to be more creative about assignments, perhaps even weaving generative AI into essay prompts, to ensure that the value of the writing process is not lost. The GAIA policy is not merely prohibitive. It rewards people who choose not to use generative AI in ways that shortcut the learning process, while also rewarding people who use it in creative ways that demonstrate ambition and ingenuity.

Some Useful Historical Analogies

We believe this computer-language example can help universities grapple with the sharp challenge that generative AI poses to the traditional role of writing in education. Like the software stack, generative AI is enlarging the “writing stack,” promising to eliminate a tremendous amount of repetitive effort from the human production of writing, particularly in business settings. This new world demands writing skills at the level of prompt engineering and checking AI-generated text — unfamiliar skills, perhaps, but vital for the future and difficult to acquire.

In educational settings, instructors produce the friction needed to spur learning in more than one way. We once learned to program in machine language, then in assembly language, then in higher-level programming languages, and now in code-eliciting prompt engineering. Each stage had its own kind of challenges, and we nodded in respect to the coders who created the compilers to translate everything at higher levels back to executable machine language. Similarly, we learned to write though being challenged to express simple ideas, then to handle syntax and grammar, then to construct complex arguments, then to master one style, and then to move easily among multiple genres. Now, thanks to generative AI, there’s another level in the writing stack, and eliciting good writing through prompt engineering is the new skill. Friction sufficient to promote learning is present at each level.

Maybe, just maybe, generative AI is exactly the kind of disruption we need.

It’s not a perfect analogy. After all, high-level coders really don’t need to know machine language, whereas high-level writers do need to know spelling, syntax, and grammar. But the analogy is useful for understanding “prompt engineering” as a new kind of coding and writing skill.

In this bizarre policy landscape, how should universities chart a way forward? How should we handle generative AIs that produce high-quality text, computer code, music, audio, and video — and overcome existing quality problems in a matter of months? That have the potential to disrupt entire industries, end familiar jobs, and create entire new professions, and that are also vulnerable to replicating the bias of our cultures in uninterpretable algorithmic behavior that is more difficult to audit than it should be?

Given the massive questions now facing us, a “pause” on advanced generative AI would be nice. But we cannot pause the impacts of generative AI in the classroom, and we are not convinced that eliminating generative AI from the learning experience is the right path.

We recommend that university leaders and instructors step way back and ask what we are trying to achieve in educating our students. To the extent that universities are merely a cog in an economic machine, training students to compete against one another for lucrative employment opportunities, making them desperate to cut corners and even cheat to inflate their GPAs, then generative AI threatens extant grading practices and undermines the trust that employers and parents vest in universities to deliver valid assessments of student performance.

But if universities are about building the capacity for adventurous creativity, cultivating virtues essential for participating in complex technological civilizations, and developing critical awareness sufficient to see through the haze of the socially constructed worlds we inhabit, then maybe we reach a different conclusion. Maybe, just maybe, generative AI is exactly the kind of disruption we need, prompting us to reclaim an ancient heritage of education that runs back to the inspirational visions of Plato and Confucius.

When students tell us they need our support to help them figure out AI, and warn us not to get stuck in our well-worn pedagogies, we think they’re doing us a great favor. We ourselves need to figure out generative AI and rethink what we’re trying to achieve as educators.