Building a Global Class Network

Member Institution

Stanford University

Case Study Lead(s)

Stanford University’s Legal Design Lab, Universidad de Los Andes, Universidad Francisco Marroquín, and Universidad Anáhuac -Querétaro

Project

Global Network

Executive Summary

The legal design lab network is an inter-university project between instructors from law and design schools across four universities that began in 2019. Stanford University’s Legal Design Lab had developed a course on court and justice innovation, that they then worked with three other universities — Universidad de Los Andes (in Colombia), Universidad Francisco Marroquín (in Guatemala), and Universidad Anáhuac -Querétaro (in México) — to teach in sync.

The instructors shared class planning, syllabi, partnership plans, and other class resources. The students in the class were all working with local partners, and they had opportunities to share their insights and work product with students in the other universities. This case study presents the narrative of the various university courses, and the insights and recommendations they have for a successful class network for other universities who may want to teach in a similar model.

The 2019 class network was a ‘prototype’ meant to explore what a more permanent network could be. The overall experience of the professors and students was positive, especially as it was the first time teaching an interdisciplinary course between law schools and design schools in the three universities. Still, each of the Mexican, Colombian, and Guatemalan schools had different difficulties along the course. These difficulties and lessons learned would make a second iteration of the course much better. The first versions of the class helped build cornerstones of more interdisciplinary, hands-on, and experiential courses in each of the universities, and the network can grow to accommodate more synced courses and independent development.

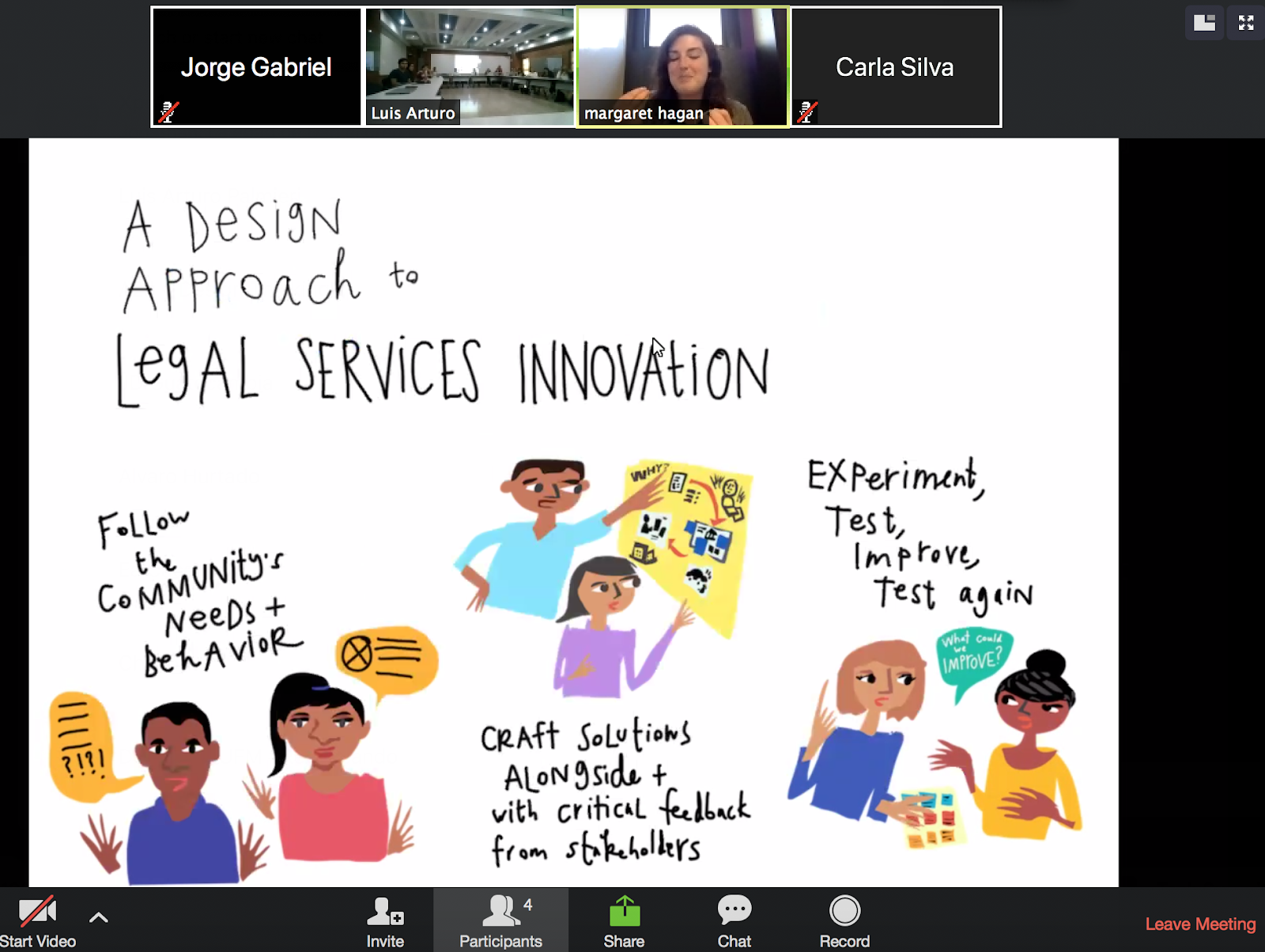

Stanford’s Legal Design Lab has been building a curriculum over the past six years to teach a mixture of service design, agile technology development, policy prototyping, and organizational change to our students.

These types of classes help to change the mindsets of students — opening up new ways of working, solving problems, and building a career. The Lab-based classes mix hands-on, client-facing work of clinics, with the systems thinking and research of policy labs, and the development focus of startup classes.

One of the core missions of the Legal Design Lab is training students and professionals in human-centered legal design. In 2018, the Lab team thought about how to scale up the impact in this mission, aside from offering more courses at Stanford. Even if the Lab’s local California courses have impact on the 20-some Stanford students in a given class and the one or two community partners, could the Lab leverage its class model to have a larger impact — on a larger number of the next generation of legal professionals?

The Lab team identified an opportunity in its many recent graduates, many of whom are LLMs or graduate students who, after graduating from Stanford, leave California for other states or countries. What if, as these students were trained them in the Stanford classes, they could also be equipped with resources and abilities to set up similar classes in other universities and groups?

In the 2017-18 school year, a number of LLM students taking Intro to Legal Design asked if it might be possible to replicate the class back in their home countries, where they had already been teaching before coming to Stanford for an LLM. Two particular students, Colombian lawyer and LLM Santiago Pardo and Mexican lawyer and LLM Manuel Mureddu, had the insight that sparked experiment over the past year. They were empowered to use design methods and make a change in their own lives, communities, and (especially) on their legal career. This is how the idea was born: How might we harness the interest of the former students and make the legal system more meaningful through human-centered design at a regional scale?

At the same time as the Lab was talking to interested students about how they might teach legal design in other universities, the Stanford team was also scoping out the next year’s classes. It had been teaching various classes on Prototyping Access to Justice, Design for Justice: Eviction and Fines and Fees — and they wanted to think about expanding out beyond just law students and ‘justice issues’.

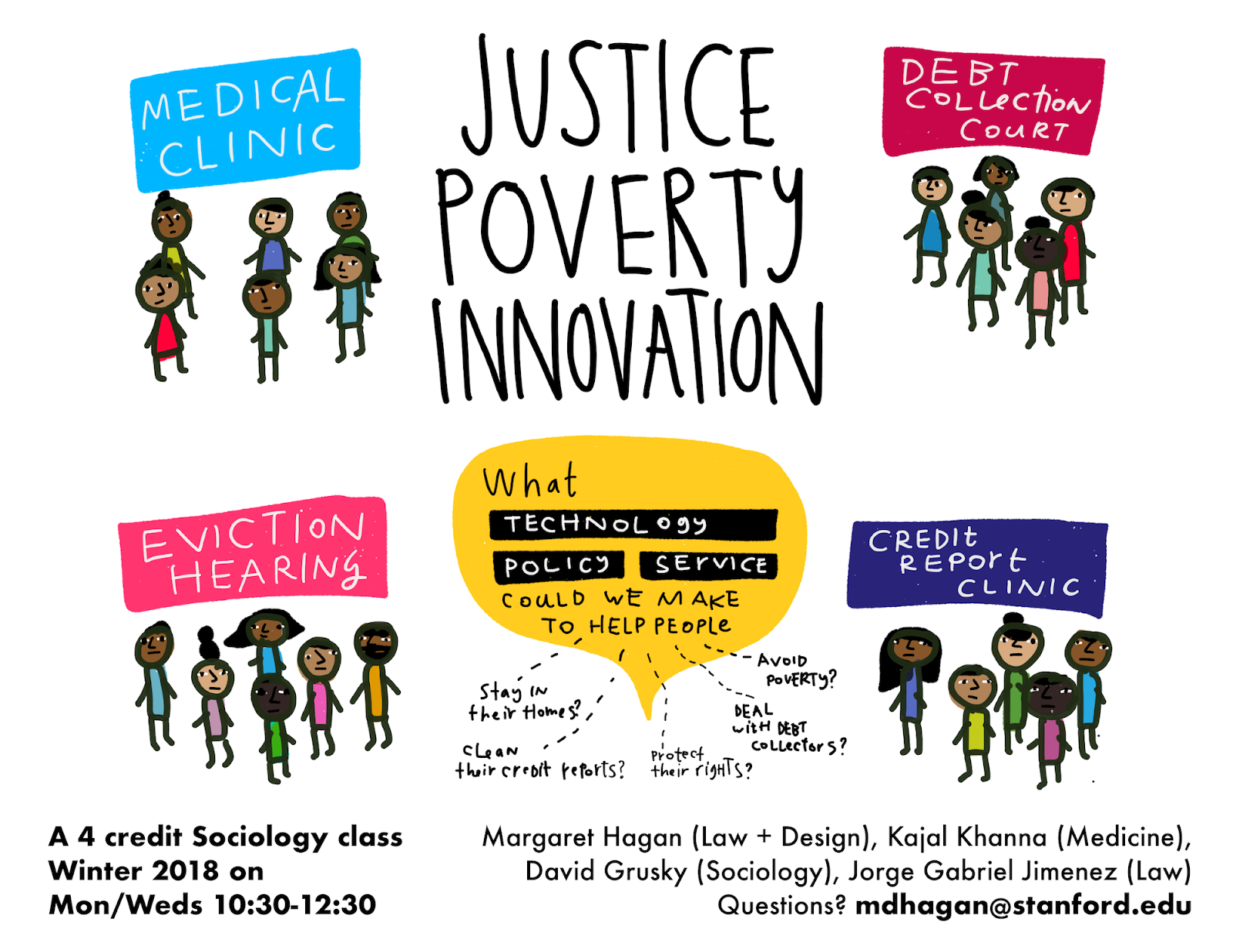

After conversations with different professors on Stanford campus, including in Sociology and the Med School, we identified the potential for a course on how emerging technologies and human-centered design could be used to help people going through problems with housing, medical care, and debt. As the team developed this new interdisciplinary class, Justice + Poverty Innovation, they thought if they could link this in with a possible inter-university network of classes.

What if there could be teams at different universities, teaching the same basic course on ‘legal design’ and ‘access to justice,’ but with local partners, policy challenges, and student group? What if law students in different countries could have a similar experience to a Stanford’s student, with the same essential curriculum structure and teaching resources, but with local partnerships and justice challenges?

The initial idea was inspired by a franchise model: to create something of a ‘franchise course’ where the Lab would be the ‘franchisor’ and could provide the syllabus model, support to teach the class, and the materials to the teaching team in each university (the franchisee) who would do all of the groundwork to establish the course, find local partners, recruit students, and facilitate the course. It wouldn’t be about a financial arrangement, but more of an Open Access model: we provide our structure, insights, and best practices in setting up a legal design lab class, and the other universities can learn from it and adapt it to their local context.

Santiago Pardo (Colombia), Maribel Cruz (Guatemala), and Manuel Mureddu (Mexico) accepted the challenge to teach the course in their respective countries.

The courses taught at the different countries needed to include six components:

- Content and overarching goals. The main goal is to teach students the design process, and how to use it to solve problems in the legal and justice system. Students would know what human-centered design is, and how to use it to understand how to communicate better, how to create new products and services, and how to reform social systems at the end of the course.

- Hands-on. The class would be hands-on, and the students would create new proposals, designs, and strategic plans. The students would have to take leadership in scoping out milestones, partnerships, and what they would be developing. The class would provide structure, coaching, resources, and connections to support them.

- Partner and real-world problem. Each university needed to work with a client or partner that needed to tackle a real-world problem related to justice. The partners included the Constitutional Court in Colombia, NGOs related to justice, and the legal clinic of the university.

- Interdisciplinary. To inspire creative thinking, the course will bring together students and faculty from different disciplines, and backgrounds. The teaching team should be interdisciplinary, and ideally the class can be cross-listed as well.

- Intercultural communication. The students and professors from the different courses would have the possibility to communicate and receive detailed and cooperative critique on their design process.

- Opt-in culture. The students and professors participated in this course because they chose to. It shouldn’t be required.

The first task for each of the potential class ‘franchisee’s was to find an anchor university that would be willing to host the course in each city. The teaching team had the objective to convince the law school dean of a university to teach a class with the characteristics outlined before. Teaching interdisciplinary courses is not common in Latin America with a tradition of rigid curriculums of Continental Law. After some meetings to explain the course, the Deans decided to join the project. The Universidad de Los Andes (in Colombia), Universidad Francisco Marroquín ( in Guatemala), and Universidad Anáhuac — Querétaro (in México) all accepted to host the course of legal design and access to justice.

Other schools from the different universities also supported the project in more particular ways. In Colombia and Mexico, the design school recommended specific professors to join the teaching team, to balance out the law school instruction with design expertise. For example, Francisco de Santiago, faculty from the design school in Uniandes was part of the teaching team. In Guatemala, the school of business, and political science encouraged their students to take the class, to ensure more of a healthy student mix.

In all three of the new classes, it was the first time that the Law Schools partnered with the other schools like the Design School to develop a course. This partnership benefited from having an interdisciplinary course with students from different backgrounds. In Colombia and Mexico, the course was composed of a mix of Law and Design students, while in Guatemala it was a mix between Law, Business, and Political Science students. It was challenging to find the right schedule that did not conflict with other student’s activities at the different schools. It turns out that listing classes across departments is a significant logistical barrier.

The teaching team in each country also reflected the interdisciplinary approach of the course which allowed the students the opportunity to learn the value of working with a multidisciplinary team. Having a ‘teaching team’ was valuable but also required an extra effort of coordination among them to work together. In most of the countries, it was the first time that they worked or taught together.

There was a minimum number of students that needed to enroll in each University to be able to open the course. The advertising campaign included posters, e-mails, articles on the university news, on-site presentations, and videos. We reached the goal at all the universities: an approximate of twenty students enrolled in each country.

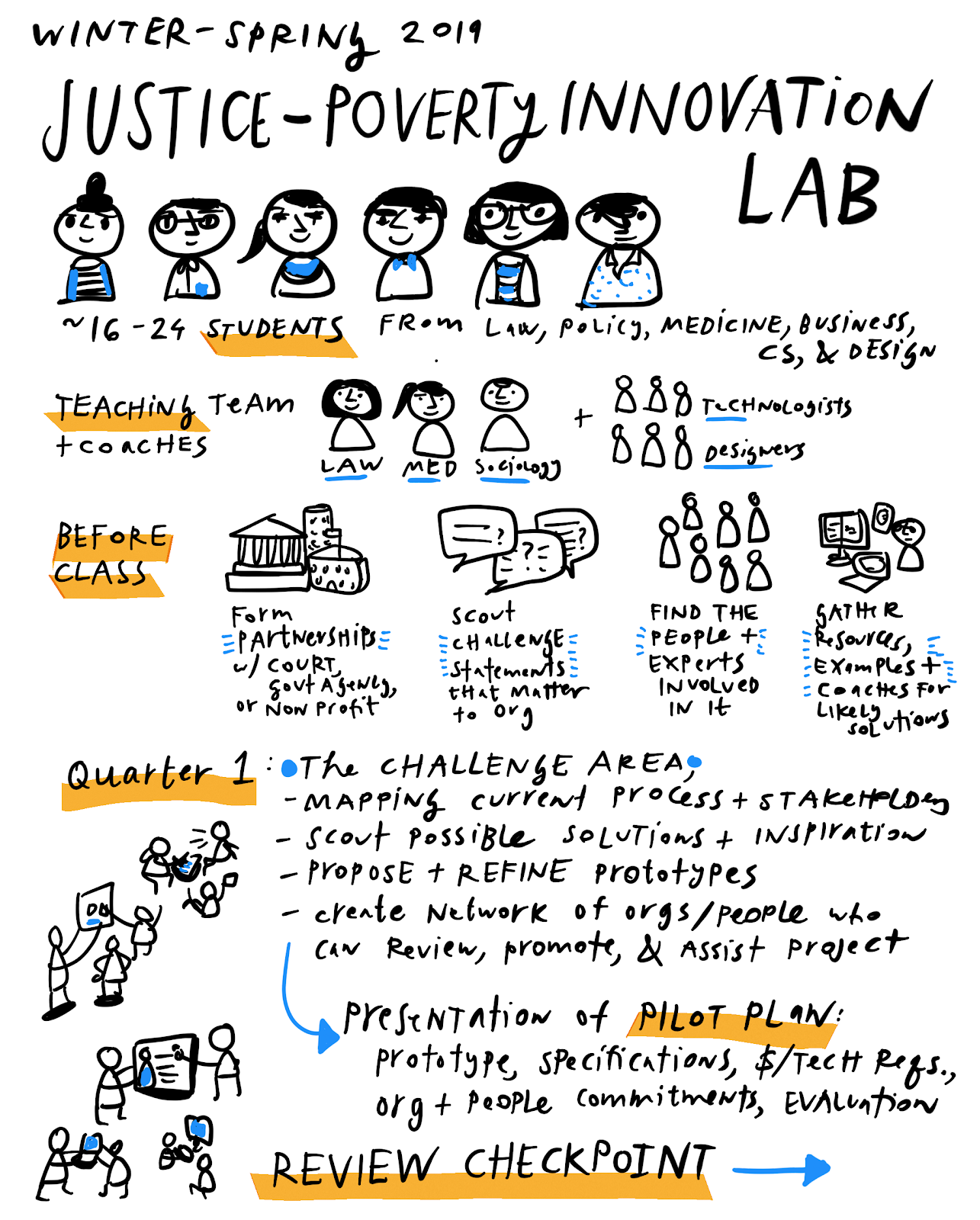

Once the class was established, there was a basic syllabus that was shared from the Stanford class team with the other universities, and then adapted into Spanish language and for the term schedule of the local universities. The basic arc of the class and network activities were same across the class:

- Part 1: Introduction to the legal design approach, the teams, the partner’s challenge.

- Part 2: Exploration of the challenge area, with user research, legal research, observations, secondary reading, interviews, etc. Create ‘understanding’ deliverables to define who the key stakeholders are, what problem framing are good opportunities, and what the landscape of past and proposed solutions are.

- Part 3: Prototyping and experimentation, with brainstorming of a range of possible solutions, trying out experiments with the partners, conducting user testing and stakeholder feedback, and understanding how early-stage ideas might be refined.

- Part 4: Refinement and pilot hand-over, to take the ideas that have received the best feedback and testing results, making them higher fidelity, and working with the partner to determine how they might be piloted, handed off, and brought to impact.

Throughout the course, the different university classes would be in communication with each other. The classes had regular feedback sessions that aimed to be cross-country design critiques. Teams in one class would share their deliverables from their work in parts 2 and 3 with other university classes, for their outsider’s perspective — and also to possibly cross-pollinate ideas on process and solutions.

The teaching team from Stanford created a large Google Drive folder in English and Spanish translations, with its course materials for an initial syncing of all the teaching teams. In addition, the teaching team members from Stanford gave initial virtual lectures in the introductory part of the course to students in the different local classes. This was to provide more detail on the background to the class and the Stanford team’s past experiences in this type of public interest design and technology work.

In addition, one Stanford teaching team member, Margaret Hagan, traveled to Colombia and taught a class to the Colombian students from Universidad de Los Andes. She also got to do a design review of their work, and connect it back to the Stanford students’ projects.